The Tardy Times

EDITORS

After 30 years at the Ex, Larry left

for Mexico – and never looked back

Larry Beaumont

Tom Fleming

August Maggy

Floyd Fessler

Bruce Hilton

P.J. Corkery

Tom Fleming

After 30 years at the Ex, Larry left

for Mexico – and never looked back

Larry Beaumont

Tom Fleming

August Maggy

Floyd Fessler

Bruce Hilton

P.J. Corkery

Tom Fleming

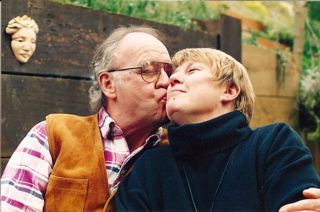

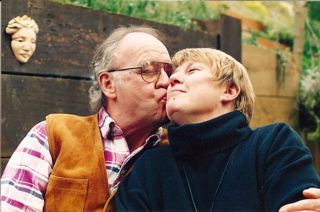

Larry Beaumont, Judy Beaumont

HE WAS the complete professional as a journalist and, in his very private personal life, a selfless benefactor of people who needed help. Larry had been the Sunday editor, sports editor and chief of the copy desk during more than 30 years at the Hearst Examiner.

HE WAS the complete professional as a journalist and, in his very private personal life, a selfless benefactor of people who needed help. Larry had been the Sunday editor, sports editor and chief of the copy desk during more than 30 years at the Hearst Examiner.

He grew up in Chicago, served in the Marine Corps and was graduated from the University of Illinois. His daughter, Jenny, wrote: “He had gone on to do graduate work in literature with a focus on Ernest Hemingway, but somewhere just before turning in his thesis he had a row with his professor and never did so.” He suffered fools, as he would put it, ungladly.

His first newspaper job was in Rockport, Ill. There he met Judy, the boss's secretary, who became his third wife in 1969. After moving to San Francisco, they bought a three-flat building in Noe Valley. They moved to Pacifica in 1989. Judy worked there as a police dispatcher, then as a city personnel clerk, while Larry climbed up and down the ladder at the Examiner.

Back when the morning copy desk was manned by men, most of them grumpy, he (and Tommy Thompson and Bruce Hilton) is remembered affectionately by desk newcomers Margo Freistadt and Bernadette Fay. To them, his attitude was welcoming and supportive. To the front office, particularly publisher Reg Murphy, he was barely civil.

Assigned to the editorial pages, he was the layout editor. He did his work efficiently but without enthusiasm, leaving promptly at lunch to have a beer at the M&M, smoke a cigarette and work the New York Times crossword. After work, he was a volunteer handyman for the elderly and disabled people in St. Paul's parish in Noe Valley and, later, in Pacifica.

When Larry retired in 1998, he didn’t look back or stay in touch. He and Judy moved to the expat community of Upper La Floresta in Ajijic near Lake Chapala, not far from Guadalajara, Mexico. They were volunteers in numerous charitable causes, especially the Programa de los Niños Incapacitados. (It helps disabled Mexican children).

Their adventure lasted only six years.

Throat cancer killed Judy in 2004.

On Aug. 3, 2005, Larry died of lung cancer.

Their daughter, Jenny, a web designer who lives in France (emailme@jennybeaumont.com), tried to inform the Chronicle about the death of the longtime Examiner editor. Nothing came of it.

His colleagues never knew.

“In all fairness to Phil Bronstein, he really can't be blamed for my father not getting his deserved obit,” she writes. “I am the slacker who didn't come through with the necessary information, the obit having been assigned to someone who didn't even know my dad, and I feeling more than a bit daunted by the task.”

Larry spent his life in the news business. This notice, three years too late, is his only obituary.

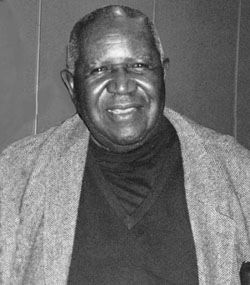

Tom Fleming

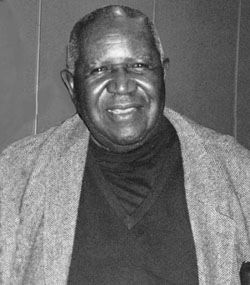

HE HATED RACISM with a passion, but he got along with everybody – including the racists. He came of age in Chico, then a little city in the orchard country of the Sacramento Valley, but as an adult he traveled the world – including Russia and Egypt and Tashkent and points between. He avoided the spotlight, but he was a friend to scores of black notables – including Jackie Robinson, Bill Robinson (Mister Bojangles), Paul Robeson, Duke Ellington, W.E.B. Du Bois, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Langston Hughes and Martin Luther King, Jr., to name a few.

Tom Fleming, whose failing health forced him to move in 2005 to San Leandro, died there on Nov. 21, 2006, just a week before his 99th birthday. The eulogies and obits focused on his remarkable achievements as editor and mainstay of the Sun Reporter newspaper and its satellite weeklies aimed at African American readers throughout the Bay Area. Few words were said about his many years as the only black reporter in the all-white pressroom in San Francisco's Hall of Justice.

eulogies and obits focused on his remarkable achievements as editor and mainstay of the Sun Reporter newspaper and its satellite weeklies aimed at African American readers throughout the Bay Area. Few words were said about his many years as the only black reporter in the all-white pressroom in San Francisco's Hall of Justice.

Peter Mellini, a history professor now retired from Sonoma State, joined us several years ago in a lengthy conversation with Tom. It was part of a series of oral history interviews with him and other police beat reporters in the days when they wore snap-brim fedoras, drank too much and laughed at everybody. Tom would spend hours every day in City Hall and the Hall of Justice to collect news and gossip from the courts, the mayor's office, the Board of Supervisors and the police blotter. And for a time, because his editorship paid so little, he worked in the district attorney's office as a bond and warrant clerk.

The pressroom bred many a story, but not necessarily for the papers. Fleming remembered the short fuse of super-grumpy Examiner police reporter Frank O'Mea (he would later have a fatal heart attack when a shouting "bullshit!" at the doctor who informed him that he had terminal cancer)...genial Harvey Wing (who never passed up a freeload)...the stuttering Stanford grad Baron Muller (who gleefully would call a police captain at home at 4 a.m., hang up without a word, call again in 5 minutes, ask him to comment about something and firmly deny that he had made the earlier call).

who informed him that he had terminal cancer)...genial Harvey Wing (who never passed up a freeload)...the stuttering Stanford grad Baron Muller (who gleefully would call a police captain at home at 4 a.m., hang up without a word, call again in 5 minutes, ask him to comment about something and firmly deny that he had made the earlier call).

Tom wrote millions of words during his 61 years at the Sun Reporter. Every week he crafted an editorial, a police log and commentary on national and world events. He also wrote “Reflections on Black History.” It's a series of vignettes from his pre-journalism youth: The time he lost his first and only boxing match, his brief career as a waiter on a Bay ferry and the boyhood day in Chico in the 1920s when he held a shotgun on his porch, waiting for the Ku Klux Klan (who thought better of it). His “Reflections,” an unfinished memoir, is available on the Web: www.freepress.org/fleming/fleming.html

“In 1935, I knew just about every black person in San Francisco,” he told us. “That changed with World War II, when blacks came in to work in the shipyards and defense industries.”

Tom said he rarely argued, although he spoke up one day when the mayor, Roger Lapham (1944-1948), asked him about the many blacks who moved from the Central Valley and the South to take defense jobs during World War II.

The mayor said, “Mister Fleming, ‘How long do think these kind of people are going to be here?’ ”

The editor answered, “. . . We are American citizens, just like you. We don't need no passports.” (Check out a clip of Tom's complete statement: www.archive.org/details/ssfTomF_1 - 14k).

More often, Fleming let his old Royal typewriter do his talking for him. It produced an endless stream of editorial comment focused on civil rights, equal opportunity and the accomplishments of the African-American community.

None of the reporters, police officials and judges of that time would be so honored as Thomas Courtney Fleming. His well-attended memorial service took place amid the granite and marble of City Hall.

Floyd Fessler

REPORTERS have all the fun. They get to tell stories. Copy editors are allowed to listen. After all, their adventures are mental. Who cares about grappling with a recalcitrant story in the quest for a memorable headline? Or making a great catch? Or undangling an embarrassing modifier?

Floyd Fessler, who died Dec. 16, 2006, at age 67, was no exception. He had to be prodded to tell about the morning that he realized every editor's dream.

Fessler, the son of the late Seattle Times columnist Floyd Fessler Sr., studied journalism at the University of Puget Sound and, after he was drafted and served his time, moved to the Bay Area and joined the staff of the Berkley Gazette. He later covered sports for the Contra Costa Times.

He worked on the copy desk of the San Francisco Examiner and as an editor for its Sunday magazine, California Living. He sailed on the Bay, listened to reggae and played chess.

When encouraged, he would recall events of Feb. 4, 1974, the day a dream came true.

It was an otherwise uneventful morning in the cramped newsroom of the Berkeley Gazette, then a struggling daily with nine more years of life. The phone rang.

A young woman had just been kidnapped from her apartment on Hillegass Street and dumped into the trunk of a car.

She was identified as Patty Hearst.

Fessler began to type, fast.

But not until he shouted.

“Stop the presses ! !”

August Maggy

YOU WON'T SEE their bylines, but good copy editors like Floyd Fessler are just as important as the writers, columnists and the big shots in the glass offices. And if the late Harry Farrell (see below) exemplified the aggressively competitive extrovert who didn't mind offending someone to get a good story, listen to what his former colleagues said about a quiet, courteous deskman.

get a good story, listen to what his former colleagues said about a quiet, courteous deskman.

August Maggy, a 60-year-old copy editor in the Chronicle's business section, died March 21, 2007, at his home in El Sobrante.

“He was the nicest guy,” said Margo Freistadt, who worked with him at the Chronicle. “A very pleasant, kind fellow,” said George Martin, who worked with him at the Chronicle and the Richmond Independent.

“August was a rarity,” said Tim Porter, who was his boss at the Independent. “A genuinely nice guy. He cared about journalism, he cared about doing good work, and he cared about his colleagues.”

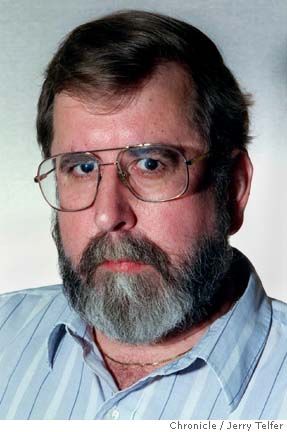

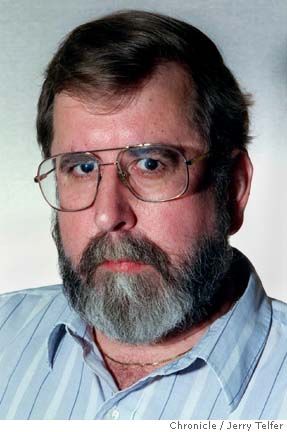

Bruce Hilton

TWO WEEKS before kidney failure took his life, Bruce Hilton told his son how he would like to be remembered. It was a surprise. That's what Paul (aka Spud) Hilton told mourners at the memorial service in Sacramento at St. Mark’s United Methodist Church on April 5, 2008.

His colleagues on the Examiner copy desk knew him as Bruce, but he was also the Rev. Mr. Hilton, an ordained minister in the United Methodist Church.

He didn’t tell Paul about his lifelong crusades for social justice, his pioneering work in bioethics, his syndicated newspaper columns or his launching of the Examiner’s AIDS Week report.

He didn't mention his courageous decision to move in 1965 with his family to Mississippi in the fight for voting rights. His advocacy for gay, lesbian and transgender people? Not a word.

He didn’t cite his passionate affair with the tuba, which prompted him 27 years ago to organize a trad jazz band, the Joyful Noise.

None of the above.

He was probably serious. Probably. He wanted to be remembered instead for one of the headlines he wrote during his parallel career at the Examiner as a copy editor of surpassing skill.

The hed, which earned him a $300 prize, ran over a news story about cops wasting too much time with coffee breaks and doughnut runs:

Much ado over gnoshing

BRUCE had been a diabetic for 37 years. His condition worsened after the death in October of his beloved wife, Virginia. Half blind, confined to a wheelchair, he refused dialysis and entered a hospice. On March 14, he died at the age of 77.

Paul, a travel writer at the Examiner, led the Joyful Noise trad jazz band at the memorial service as vocalist and cornet player (from Psalm 100: “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord . . .”) In the fast-fading world of traditional jazz, mostly kept alive by white musicians, the tuba is unobtrusively crucial to the tunes created by black musicians a century ago in the sporting houses and saloons of New Orleans. The band plays gospel songs (along with the, er, secular tunes) in churches, house parties and festivals.

at the memorial service as vocalist and cornet player (from Psalm 100: “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord . . .”) In the fast-fading world of traditional jazz, mostly kept alive by white musicians, the tuba is unobtrusively crucial to the tunes created by black musicians a century ago in the sporting houses and saloons of New Orleans. The band plays gospel songs (along with the, er, secular tunes) in churches, house parties and festivals.

The band has a gig on the third Sunday of every month at Champa restaurant in El Sobrante. It’s a truly multicultural event – trad jazz for 1920s dancing in an Indian restaurant with a Hispanic name that specializes in pizza. Even after diabetes forced him into a wheelchair, Bruce happily laid down the baseline – and bass line – for “The Saints Go Marching In,” “Hong Kong Blues” and “A Closer Walk with Thee.”

As Bruce could no longer drive, his chauffeur for band gigs was his remarkable wife of 55 years. Virginia was still a nursing student when they married in 1952. She died Oct. 7, 2007, of complications linked to breast and bone cancers – the same lethal disease that dominated her 20-year career as a nurse in the oncology wards.

Leaving the healing profession at age 45 to enroll in theological studies, she was ordained in the Methodist ministry in 1980. Few women were then Methodist pastors. A lifelong activist in causes for civil rights, she served in Bay Area churches before she was assigned to Faith Methodist in Sacramento. The commute to San Francisco was too much for Bruce, who retired. They stayed in Sacramento after Virginia also retired in 1996.

Bruce had outlived most of his fellow Examiner editors: DeWitt Scott, George (Tommy) Thompson, Larry Beaumont and others. It was up to his fellow bioethicists and pastors to say what few of the journalists knew about Bruce.

“He was a giant,” said Rev. Dave MacMurdo, “and a national treasure.”

Other editors

CANCER on Nov. 16, 2007, took the life of Dan Cook, 65, the raconteur/chef who was an editor and writer for the San Mateo Times . . . Bronwen Todd, 58, widow of Examiner deputy city editor John Todd, died April 17, 2007, of kidney failure . . . Cathy Schutz, an assistant features editor and former city editor at the Tribune, died Nov. 17, 2007, of breast cancer. She was a veteran of the Daily Cal and the old Richmond Independent and Berkeley Daily Gazette. She had been a volunteer for 30 years with the Contra Costa Civic Theater in El Cerrito . . . Someone had to make the copy continue to flow during the San Jose Mercury's transition from laughing stock to stock options. Russ Robertson, a deskman from 1959 until he retired in 1979, is remembered by colleagues as “cool-head and patient,” “soft-spoken” and ahead of his time in treating “women with great respect – as equals.” He was 90 when felled by brain hemorrhage on March 28, 2007, at his home in Fremont. He lived long enough to see that stock manipulations had led to new ownership of the Merc. He got out while the getting was good . . . Frank H. Delaplane, a Chronicle reporter in the 1950s, must have wearied of barbs that he got his job because of his Chronicle dad, Pulitizer Prize-winning Stanton Delaplane. He went back to Reno, where he had paid his way through the University of Nevada as casino pit boss. By the time he left in 1979 for Washington. D.C., and the Gannett News Service, he was managing editor of the Nevada State Journal and Reno Evening Gazette. Multiple sclerosis forced him into retirement in 1986. He died Aug. 4 in Reno. . . . Al Burgin, one of the last set-’em-up regulars of the Jerry and Johnny saloon on Third Street, spent almost 20 years as an editor at the Hearst Examiner before moving into advertising and PR. He later founded the Commuter Times, a Novato-based weekly. He died June 6 in San Rafael.

HE WAS the complete professional as a journalist and, in his very private personal life, a selfless benefactor of people who needed help. Larry had been the Sunday editor, sports editor and chief of the copy desk during more than 30 years at the Hearst Examiner.

HE WAS the complete professional as a journalist and, in his very private personal life, a selfless benefactor of people who needed help. Larry had been the Sunday editor, sports editor and chief of the copy desk during more than 30 years at the Hearst Examiner. He grew up in Chicago, served in the Marine Corps and was graduated from the University of Illinois. His daughter, Jenny, wrote: “He had gone on to do graduate work in literature with a focus on Ernest Hemingway, but somewhere just before turning in his thesis he had a row with his professor and never did so.” He suffered fools, as he would put it, ungladly.

His first newspaper job was in Rockport, Ill. There he met Judy, the boss's secretary, who became his third wife in 1969. After moving to San Francisco, they bought a three-flat building in Noe Valley. They moved to Pacifica in 1989. Judy worked there as a police dispatcher, then as a city personnel clerk, while Larry climbed up and down the ladder at the Examiner.

Back when the morning copy desk was manned by men, most of them grumpy, he (and Tommy Thompson and Bruce Hilton) is remembered affectionately by desk newcomers Margo Freistadt and Bernadette Fay. To them, his attitude was welcoming and supportive. To the front office, particularly publisher Reg Murphy, he was barely civil.

Assigned to the editorial pages, he was the layout editor. He did his work efficiently but without enthusiasm, leaving promptly at lunch to have a beer at the M&M, smoke a cigarette and work the New York Times crossword. After work, he was a volunteer handyman for the elderly and disabled people in St. Paul's parish in Noe Valley and, later, in Pacifica.

When Larry retired in 1998, he didn’t look back or stay in touch. He and Judy moved to the expat community of Upper La Floresta in Ajijic near Lake Chapala, not far from Guadalajara, Mexico. They were volunteers in numerous charitable causes, especially the Programa de los Niños Incapacitados. (It helps disabled Mexican children).

Their adventure lasted only six years.

Throat cancer killed Judy in 2004.

On Aug. 3, 2005, Larry died of lung cancer.

Their daughter, Jenny, a web designer who lives in France (emailme@jennybeaumont.com), tried to inform the Chronicle about the death of the longtime Examiner editor. Nothing came of it.

His colleagues never knew.

“In all fairness to Phil Bronstein, he really can't be blamed for my father not getting his deserved obit,” she writes. “I am the slacker who didn't come through with the necessary information, the obit having been assigned to someone who didn't even know my dad, and I feeling more than a bit daunted by the task.”

Larry spent his life in the news business. This notice, three years too late, is his only obituary.

Tom Fleming

HE HATED RACISM with a passion, but he got along with everybody – including the racists. He came of age in Chico, then a little city in the orchard country of the Sacramento Valley, but as an adult he traveled the world – including Russia and Egypt and Tashkent and points between. He avoided the spotlight, but he was a friend to scores of black notables – including Jackie Robinson, Bill Robinson (Mister Bojangles), Paul Robeson, Duke Ellington, W.E.B. Du Bois, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Langston Hughes and Martin Luther King, Jr., to name a few.

Tom Fleming, whose failing health forced him to move in 2005 to San Leandro, died there on Nov. 21, 2006, just a week before his 99th birthday. The

eulogies and obits focused on his remarkable achievements as editor and mainstay of the Sun Reporter newspaper and its satellite weeklies aimed at African American readers throughout the Bay Area. Few words were said about his many years as the only black reporter in the all-white pressroom in San Francisco's Hall of Justice.

eulogies and obits focused on his remarkable achievements as editor and mainstay of the Sun Reporter newspaper and its satellite weeklies aimed at African American readers throughout the Bay Area. Few words were said about his many years as the only black reporter in the all-white pressroom in San Francisco's Hall of Justice.Peter Mellini, a history professor now retired from Sonoma State, joined us several years ago in a lengthy conversation with Tom. It was part of a series of oral history interviews with him and other police beat reporters in the days when they wore snap-brim fedoras, drank too much and laughed at everybody. Tom would spend hours every day in City Hall and the Hall of Justice to collect news and gossip from the courts, the mayor's office, the Board of Supervisors and the police blotter. And for a time, because his editorship paid so little, he worked in the district attorney's office as a bond and warrant clerk.

><

THE PRESSROOM is pretty much empty in these days of languid attention to crime news. Other reasons: Staff cutbacks, lack of serious competition and the outsourcing of telephone beat checks to the underpaid, overworked young people at Bay City News. Back in the day, however, the police beat was staffed in the 1940s and 1950s by the four daily newspapers, usually in two shifts of legmen. They were ordered to get the news first. (Instead, they tended to share and share alike. This would allow more time for poker.)The pressroom bred many a story, but not necessarily for the papers. Fleming remembered the short fuse of super-grumpy Examiner police reporter Frank O'Mea (he would later have a fatal heart attack when a shouting "bullshit!" at the doctor

who informed him that he had terminal cancer)...genial Harvey Wing (who never passed up a freeload)...the stuttering Stanford grad Baron Muller (who gleefully would call a police captain at home at 4 a.m., hang up without a word, call again in 5 minutes, ask him to comment about something and firmly deny that he had made the earlier call).

who informed him that he had terminal cancer)...genial Harvey Wing (who never passed up a freeload)...the stuttering Stanford grad Baron Muller (who gleefully would call a police captain at home at 4 a.m., hang up without a word, call again in 5 minutes, ask him to comment about something and firmly deny that he had made the earlier call). Tom wrote millions of words during his 61 years at the Sun Reporter. Every week he crafted an editorial, a police log and commentary on national and world events. He also wrote “Reflections on Black History.” It's a series of vignettes from his pre-journalism youth: The time he lost his first and only boxing match, his brief career as a waiter on a Bay ferry and the boyhood day in Chico in the 1920s when he held a shotgun on his porch, waiting for the Ku Klux Klan (who thought better of it). His “Reflections,” an unfinished memoir, is available on the Web: www.freepress.org/fleming/fleming.html

“In 1935, I knew just about every black person in San Francisco,” he told us. “That changed with World War II, when blacks came in to work in the shipyards and defense industries.”

><

WHEN HE walked into City Hall in those days, he quietly endured the not-so-subtle humiliations of oblivious politicians, bureaucrats and lawyers in a city – and an era – where white superiority was taken for granted.Tom said he rarely argued, although he spoke up one day when the mayor, Roger Lapham (1944-1948), asked him about the many blacks who moved from the Central Valley and the South to take defense jobs during World War II.

The mayor said, “Mister Fleming, ‘How long do think these kind of people are going to be here?’ ”

The editor answered, “. . . We are American citizens, just like you. We don't need no passports.” (Check out a clip of Tom's complete statement: www.archive.org/details/ssfTomF_1 - 14k).

More often, Fleming let his old Royal typewriter do his talking for him. It produced an endless stream of editorial comment focused on civil rights, equal opportunity and the accomplishments of the African-American community.

None of the reporters, police officials and judges of that time would be so honored as Thomas Courtney Fleming. His well-attended memorial service took place amid the granite and marble of City Hall.

Floyd Fessler

REPORTERS have all the fun. They get to tell stories. Copy editors are allowed to listen. After all, their adventures are mental. Who cares about grappling with a recalcitrant story in the quest for a memorable headline? Or making a great catch? Or undangling an embarrassing modifier?

Floyd Fessler, who died Dec. 16, 2006, at age 67, was no exception. He had to be prodded to tell about the morning that he realized every editor's dream.

Fessler, the son of the late Seattle Times columnist Floyd Fessler Sr., studied journalism at the University of Puget Sound and, after he was drafted and served his time, moved to the Bay Area and joined the staff of the Berkley Gazette. He later covered sports for the Contra Costa Times.

He worked on the copy desk of the San Francisco Examiner and as an editor for its Sunday magazine, California Living. He sailed on the Bay, listened to reggae and played chess.

When encouraged, he would recall events of Feb. 4, 1974, the day a dream came true.

It was an otherwise uneventful morning in the cramped newsroom of the Berkeley Gazette, then a struggling daily with nine more years of life. The phone rang.

A young woman had just been kidnapped from her apartment on Hillegass Street and dumped into the trunk of a car.

She was identified as Patty Hearst.

Fessler began to type, fast.

But not until he shouted.

“Stop the presses ! !”

August Maggy

YOU WON'T SEE their bylines, but good copy editors like Floyd Fessler are just as important as the writers, columnists and the big shots in the glass offices. And if the late Harry Farrell (see below) exemplified the aggressively competitive extrovert who didn't mind offending someone to

get a good story, listen to what his former colleagues said about a quiet, courteous deskman.

get a good story, listen to what his former colleagues said about a quiet, courteous deskman. August Maggy, a 60-year-old copy editor in the Chronicle's business section, died March 21, 2007, at his home in El Sobrante.

“He was the nicest guy,” said Margo Freistadt, who worked with him at the Chronicle. “A very pleasant, kind fellow,” said George Martin, who worked with him at the Chronicle and the Richmond Independent.

“August was a rarity,” said Tim Porter, who was his boss at the Independent. “A genuinely nice guy. He cared about journalism, he cared about doing good work, and he cared about his colleagues.”

Bruce Hilton

TWO WEEKS before kidney failure took his life, Bruce Hilton told his son how he would like to be remembered. It was a surprise. That's what Paul (aka Spud) Hilton told mourners at the memorial service in Sacramento at St. Mark’s United Methodist Church on April 5, 2008.

His colleagues on the Examiner copy desk knew him as Bruce, but he was also the Rev. Mr. Hilton, an ordained minister in the United Methodist Church.

He didn’t tell Paul about his lifelong crusades for social justice, his pioneering work in bioethics, his syndicated newspaper columns or his launching of the Examiner’s AIDS Week report.

He didn't mention his courageous decision to move in 1965 with his family to Mississippi in the fight for voting rights. His advocacy for gay, lesbian and transgender people? Not a word.

He didn’t cite his passionate affair with the tuba, which prompted him 27 years ago to organize a trad jazz band, the Joyful Noise.

None of the above.

He was probably serious. Probably. He wanted to be remembered instead for one of the headlines he wrote during his parallel career at the Examiner as a copy editor of surpassing skill.

The hed, which earned him a $300 prize, ran over a news story about cops wasting too much time with coffee breaks and doughnut runs:

Much ado over gnoshing

BRUCE had been a diabetic for 37 years. His condition worsened after the death in October of his beloved wife, Virginia. Half blind, confined to a wheelchair, he refused dialysis and entered a hospice. On March 14, he died at the age of 77.

Paul, a travel writer at the Examiner, led the Joyful Noise trad jazz band

at the memorial service as vocalist and cornet player (from Psalm 100: “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord . . .”) In the fast-fading world of traditional jazz, mostly kept alive by white musicians, the tuba is unobtrusively crucial to the tunes created by black musicians a century ago in the sporting houses and saloons of New Orleans. The band plays gospel songs (along with the, er, secular tunes) in churches, house parties and festivals.

at the memorial service as vocalist and cornet player (from Psalm 100: “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord . . .”) In the fast-fading world of traditional jazz, mostly kept alive by white musicians, the tuba is unobtrusively crucial to the tunes created by black musicians a century ago in the sporting houses and saloons of New Orleans. The band plays gospel songs (along with the, er, secular tunes) in churches, house parties and festivals. The band has a gig on the third Sunday of every month at Champa restaurant in El Sobrante. It’s a truly multicultural event – trad jazz for 1920s dancing in an Indian restaurant with a Hispanic name that specializes in pizza. Even after diabetes forced him into a wheelchair, Bruce happily laid down the baseline – and bass line – for “The Saints Go Marching In,” “Hong Kong Blues” and “A Closer Walk with Thee.”

As Bruce could no longer drive, his chauffeur for band gigs was his remarkable wife of 55 years. Virginia was still a nursing student when they married in 1952. She died Oct. 7, 2007, of complications linked to breast and bone cancers – the same lethal disease that dominated her 20-year career as a nurse in the oncology wards.

Leaving the healing profession at age 45 to enroll in theological studies, she was ordained in the Methodist ministry in 1980. Few women were then Methodist pastors. A lifelong activist in causes for civil rights, she served in Bay Area churches before she was assigned to Faith Methodist in Sacramento. The commute to San Francisco was too much for Bruce, who retired. They stayed in Sacramento after Virginia also retired in 1996.

Bruce had outlived most of his fellow Examiner editors: DeWitt Scott, George (Tommy) Thompson, Larry Beaumont and others. It was up to his fellow bioethicists and pastors to say what few of the journalists knew about Bruce.

“He was a giant,” said Rev. Dave MacMurdo, “and a national treasure.”

Other editors

CANCER on Nov. 16, 2007, took the life of Dan Cook, 65, the raconteur/chef who was an editor and writer for the San Mateo Times . . . Bronwen Todd, 58, widow of Examiner deputy city editor John Todd, died April 17, 2007, of kidney failure . . . Cathy Schutz, an assistant features editor and former city editor at the Tribune, died Nov. 17, 2007, of breast cancer. She was a veteran of the Daily Cal and the old Richmond Independent and Berkeley Daily Gazette. She had been a volunteer for 30 years with the Contra Costa Civic Theater in El Cerrito . . . Someone had to make the copy continue to flow during the San Jose Mercury's transition from laughing stock to stock options. Russ Robertson, a deskman from 1959 until he retired in 1979, is remembered by colleagues as “cool-head and patient,” “soft-spoken” and ahead of his time in treating “women with great respect – as equals.” He was 90 when felled by brain hemorrhage on March 28, 2007, at his home in Fremont. He lived long enough to see that stock manipulations had led to new ownership of the Merc. He got out while the getting was good . . . Frank H. Delaplane, a Chronicle reporter in the 1950s, must have wearied of barbs that he got his job because of his Chronicle dad, Pulitizer Prize-winning Stanton Delaplane. He went back to Reno, where he had paid his way through the University of Nevada as casino pit boss. By the time he left in 1979 for Washington. D.C., and the Gannett News Service, he was managing editor of the Nevada State Journal and Reno Evening Gazette. Multiple sclerosis forced him into retirement in 1986. He died Aug. 4 in Reno. . . . Al Burgin, one of the last set-’em-up regulars of the Jerry and Johnny saloon on Third Street, spent almost 20 years as an editor at the Hearst Examiner before moving into advertising and PR. He later founded the Commuter Times, a Novato-based weekly. He died June 6 in San Rafael.

Thirty

tardytimes.com

September 2008

tardytimes.com

September 2008